Homesteading

Fermentation: The Latest Food Preparation Trend

An hour outside of Nashville, Tennessee, down a dirt road and up a steep, curving hill in the woods, you’ll find fermentation guru Sandor Katz in a solar-powered log cabin cooking goat testicles for lunch.

The 12 students accepted to Katz’s early summer 3-week fermentation residency eagerly crowd around the kitchen table, watching him trim and slice the bulbous product, a gift from a nearby farmer friend. “They look kind of like onions?” one student muses. Surprising these students isn’t easy.

They have come from as far as Costa Rica and Germany to pitch tents outside this log cabin and learn, in essence, how to incubate bacteria and grow mold into edible delicacies from the master himself.

It’s hard to call one of the oldest forms of food preparation a trend, but home fermentation has been rising in popularity in recent years, among everyone from health-conscious foodies to high-end chefs. This is in part an effort to reclaim something lost in the generations raised on convenience and processed foods. “In the last 15 years, we’re waking up,” says Katz, who rose to prominence with the best-selling cookbooks “Wild Fermentation” and “The Art of Fermentation.” “Now it’s, OK, convenience is great, but what are the downsides? It’s nutritionally deficient? Are the methods for more production environmentally destructive?”

The answers to these questions are driving more and more people to the kitchen. Katz’s kitchen, in particular.

Katz’s residents, for reasons varying as much as their origins, find themselves incubating tempeh by day and sleeping in tents in rural Tennessee by night. There are professional chefs and amateur enthusiasts. One student works for hospice care in Oregon, another is a nurse from Cincinnati, Ohio. They came to satisfy their own curiosity, to improve their understanding of the science of edible bacteria, to get healthier and to reclaim what they consider a lost art. Many came because they want to be more self-sufficient in a world of uncertainty — uncertain weather, growing conditions and food sourcing.

“My boyfriend and I are committed to growing our own food,” says Eileen Richardson, a young chef who enrolled in the residency to help her prepare to open a kombucha café in a fermentation bar in Denver. “We don’t feel safe depending on anyone else. I want to be self-sufficient in a real way. It’s empowering.”

Katz, who is 52 and sports a striking, bushy mustache, grew up on the Upper West Side of Manhattan with parents who were both good cooks, his father the more experimental of the two. After attending Brown University, where he studied history, Katz worked at the Manhattan Borough President’s Office.

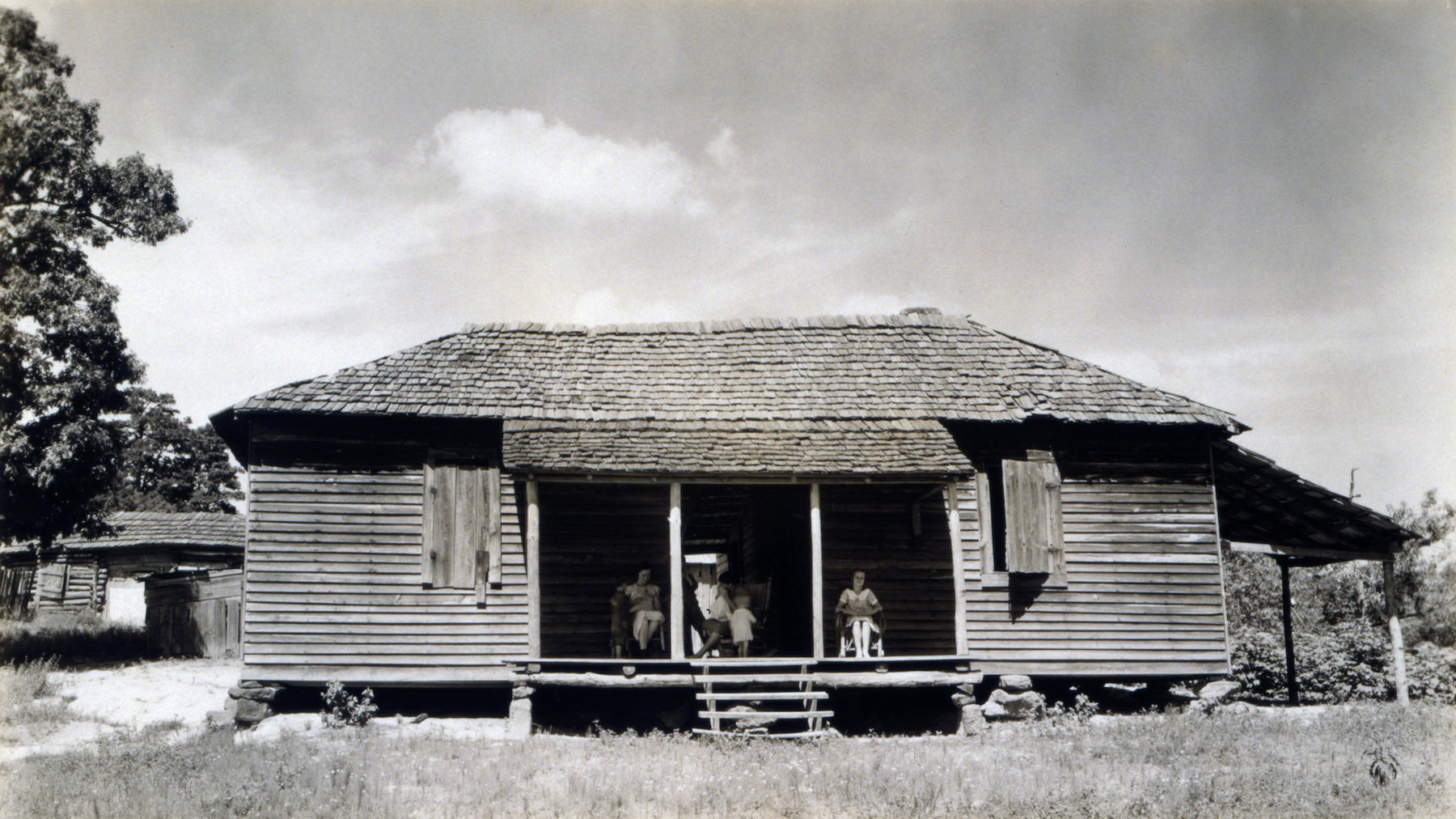

“I was a policy wonk,” he laughs. But in 1991, he was diagnosed with HIV, and by 1993, he’d left the city for Cannon County, Tennessee. That’s where he got into fermentation. Eating live-culture foods, he says, has been a part of his healing. In Tennessee he lived in an intentional community of largely queer men, women and transgendered people on 200 acres of lush, off-grid land — and began to garden. “And suddenly there was this row of cabbage and I wanted to do something with it,” he says. “I was a city kid. I hadn’t thought of what would happen when a row of cabbage is all ready at the same time, that fleeting abundance of the garden.”

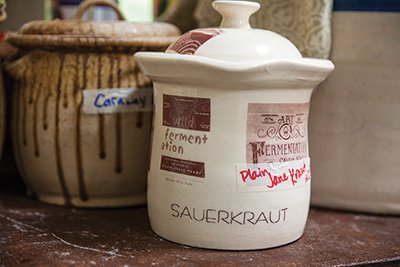

He started with sauerkraut. He made so much sauerkraut, he says, friends called him “Sandorkraut.”

Fermentation is now his life’s work. When he began teaching fermentation workshops, Katz was surprised by the fear exhibited by his students, namely a fear of bacteria. To combat the notion (as he writes in “The Art of Fermention”) that bacteria are “our enemies,” he holds classes and workshops around the world, traveling for roughly half of the year. His books have won James Beard Awards and been New York Times bestsellers. “‘The Art of Fermentation’ is an inspiring book, and I mean that literally,” writes Michael Pollan in the forward. “The book has inspired me to do things I’ve never done before, and probably never would have done if I hadn’t read it.”

“He lives his teaching,” says Laura Killingbeck, one of Katz’s fermentation residents, who traveled to Tennessee from Costa Rica, where she cooks for a ranch community. “I aspire to that.”

After the goat testicle lunch, the students again surround the kitchen table, watching Katz demonstrate how to make a wild hodgepodge of fermented beverages.

First he pours a bubbling vat of sweetened raspberry liquid through a sieve into old Pepsi bottles; the next day it will be a lightly carbonated soft drink. He transfers another vigorously bubbling crock of liquid — a mead, made with only honey, water and grapes — into a glass carboy to ferment. (“Half of the alcohol happens in the first week to 10 days,” he says). He hands out samples of a tropical beer called “mavi,” a rye bread-based drink called “kvass” and a kombucha, or fermented sweet tea, the class made the day before. (“It’s beginning to taste alive!” he says happily.) Together, the class starts on a ginger beer, made with a starter called a “ginger bug.”

“How much sugar did you put in?” asks Mike Moyer, the nurse from Cincinnati, who sits shirtless on a stool in the muggy Tennessee heat.

“Good question,” says Katz, shrugging. Fermentation, after all, is as much art as science.

Source: ModernFarmer.com

-

Do It Yourself7 months ago

Do It Yourself7 months agoParacord Projects | 36 Cool Paracord Ideas For Your Paracord Survival Projects

-

Do It Yourself9 months ago

Do It Yourself9 months agoHow To Make Paracord Survival Bracelets | DIY Survival Prepping

-

Do It Yourself9 months ago

Do It Yourself9 months ago21 Home Remedies For Toothache Pain Relief

-

Do It Yourself10 months ago

Do It Yourself10 months agoSurvival DIY: How To Melt Aluminum Cans For Casting

-

Exports8 months ago

Exports8 months agoAre Switchblades Legal? Knife Laws By State

Pingback: Cooking On The Move; Do You Consider Yourself A Campfire Chef?

Pingback: Cooking On The Move; Do You Consider Yourself A Campfire Chef? - Survive!

Pingback: Cooking On The Move; Do You Consider Yourself A Campfire Chef? | survivalisthandbook.com

Pingback: Cooking On The Move; Do You Consider Yourself A Campfire Chef?